Amy Kaser grows wheat with her father in Wasco County, near the Dalles, Oregon. In the 1990s, USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service helped farmers in Wasco County switch to no-till. Since then, the Kasers have seen benefits such as reduced erosion and increased resilience to weather extremes. As the climate changes and extreme weather events become more frequent, this practice is helping the Kaser family’s farm continue to be productive and survive more climate variability.

Interaction Time | 11 minutes

Management Goals | Increase resilience of wheat production to climate variability

Audience | Farmers and advisors, Extension, Natural Resource Conservation Service

Project Contact | Emily Huth (NRCS Conservationist); Amy Kaser

Project Area | Kaser Diamond K Farm in Wasco County, Oregon

Funding | See funding section

No-till and Climate Change

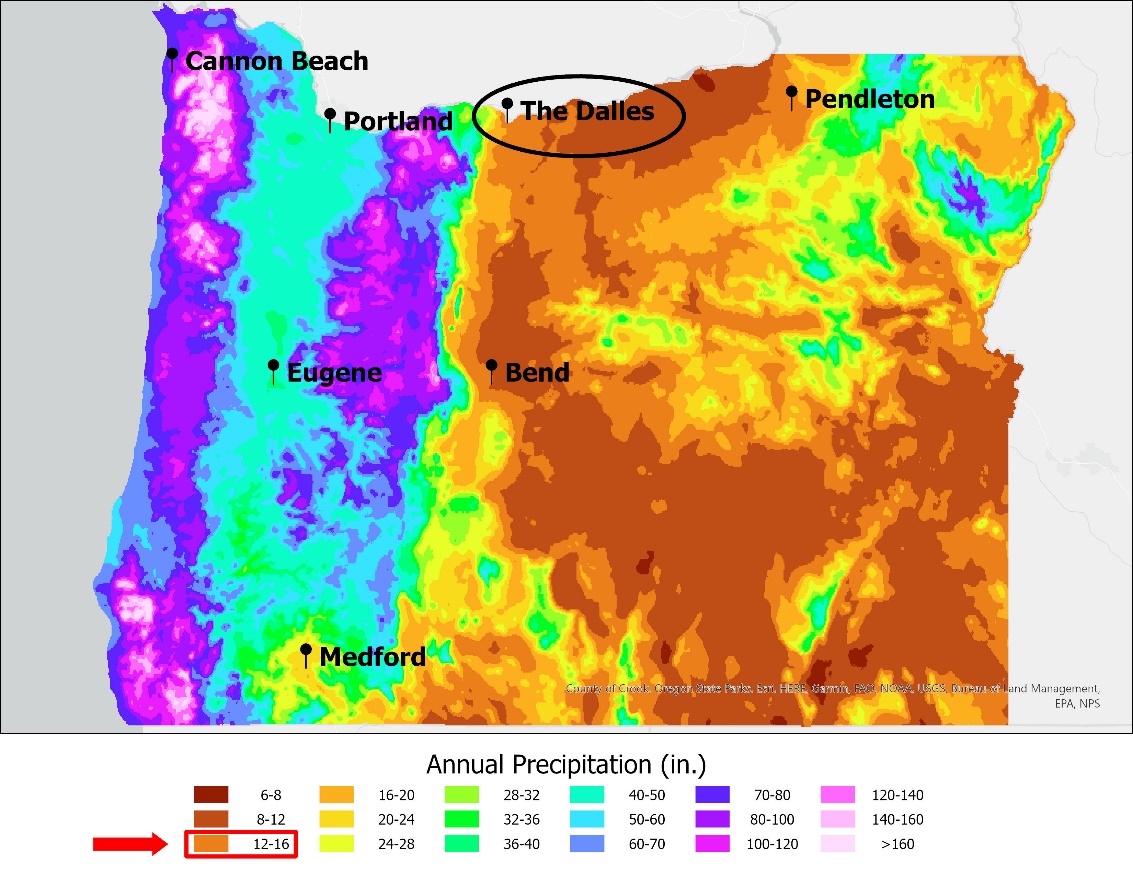

The Dalles, Oregon lies east of the Cascade Mountain Range. This region receives about 12-14 inches of rain annually, which is about 30 inches less than Portland, Oregon. Because of the dry climate, Amy Kaser and her family grow dryland wheat at their farm, which depends only on the moisture from rainfall. Farmers who grow dryland wheat usually leave fields fallow (meaning they do not grow anything on them) for a year after farming to replenish soil moisture and nutrients.

Farmers like Amy have been using no-till for many years in this region. This farming practice leaves plant residue on the ground for an entire year after harvesting. At the end of the year, farmers use a special machine that seeds the field without tilling. During that year, plant residue slowly decomposes into the soil, protects the soil from nutrient loss and drying by the sun, adds nutrients, and accumulates organic matter that also helps the soil retain more water. No-till farming also provides protection for the soil from rain or high winds that would erode it.

Amy Kaser’s family originally switched to no-till to prevent the loss of topsoil, but this practice is also helping farmers adapt to a changing climate. As weather patterns change in the Northwest, there will be more extremes ― drier times will be drier and wetter times wetter. Amy Kaser notes that they have also seen more variation, making it hard to predict what each year will hold. As these changes occur, having farms that are more resilient to extreme weather and higher levels of variability will be important for farmers livelihoods. No-till allows farms like Amy Kaser’s to be prepared for these future challenges.

Challenges and Opportunities

The change to no-till has been extremely beneficial for the Kaser family farm. The main challenge came from the switch to no-till from their previous farming practices. She noted that in order to plant wheat in untilled soil, they needed specialized equipment. This equipment was very expensive, but they had help with funding from the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS).

Farmers Helping Fish

Amy Kaser notes that outside of the benefits for dealing with more extreme and variable weather patterns, no-till farming has provided an opportunity to protect local fish populations. Reduced erosion means less sediment ends up in nearby creeks. This change has helped improve conditions for the vulnerable steelhead population in Fifteenmile Creek.

Another opportunity that has arisen from the work with no-till is the increased awareness and interest in helping the local fish population. As farmers worked to reduce erosion with no-till, they also became more involved in restoring their local watershed. Farmers have worked with organizations like NRCS, USDA Farm Service Agency, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon Soil and Water Conservation District, and others to plant trees and prevent cows from grazing in the creek. Many farmers also participate in Fifteenmile Action to Stabilize Temperature (FAST), a program that allows them to voluntarily stop pulling water for irrigation on days that go above a certain temperature threshold. This ensures that cool water can stay in the creek to support fish populations.

As climate change makes streams warmer, salmon will struggle to survive in some places. The actions farmers are taking will help to reduce fish stress in the hotter months. No-till farming helps to reduce erosion, and stream restoration allows riparian vegetation to grow and shade the water. These practices lead to better habitat for spawning salmon and improve conditions for hatchling fish, increasing their ability to thrive in the future.

Funding

For Amy Kaser and her family, the NRCS was an integral part of transitioning to no-till. In the early 2000s, the local NRCS office obtained funds to help farmers transition to this farming practice. Most of the funding provided by NRCS was through Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). The funds helped farmers purchase no-till machinery. Without NRCS’s financial assistance, farmers would not have been able to afford these machines. In addition to finding funding, NRCS personnel hosted many educational and planning sessions with farmers to get them enrolled in EQIP and CSP.

Farmers in The Dalles have also been encouraged to voluntarily reduce irrigation water use on hot days through Fifteenmile Action to Stabilize Temperature (FAST), which is funded through Soil and Water Conservation District and the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board. This program uses a model that can project water temperatures. The model determines when stream temperatures may become too warm for fish, and farmers can choose to not pull water on those days to reduce stream temperatures. It was created in collaboration with The Freshwater Trust, Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, the Oregon Water Resources Department, Wasco County Soil and Water Conservation District, and the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board.

Stream fencing and rehabilitation was funded by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, with funding from Bonneville Power Administration on some farms. As the work progressed, the USDA's Farm Service Agency also funded the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP), which helped pay for fencing and tree planting, and continues to compensate for maintenance of the riparian buffers to this day. The Soil and Water Conservation District and NRCS help by writing conservation plans for the CREP acres.