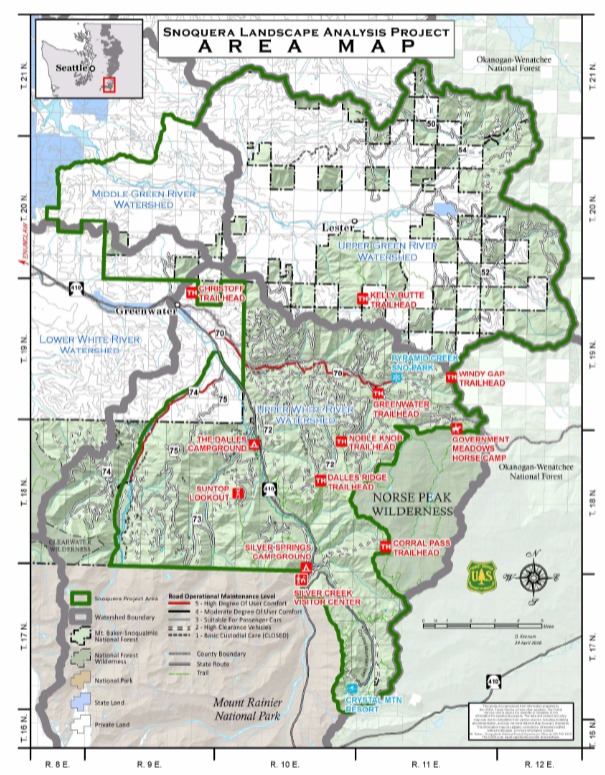

In the Snoqualmie Ranger District of the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, Forest staff and partners are preparing the Forest, its watersheds, and its road system for climate change. To understand how climate change will affect the Forest, resource staff used a vulnerability assessment paired with other analyses. The Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest is using this information to help prioritize management activities, including decommissioning roads, repositioning of dispersed campsites, adjusting culverts, and restoring streams. These activities will be incorporated into projects like the Snoquera Landscape Analysis Project.

Reading Time | 9 minutes

Management Goal | Use a climate vulnerability assessment to prioritize road and stream restoration projects

Audience | Foresters, land managers

Project Contact | Kevin James; Richard Vacirca; Karen Chang

Project Area | Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, Washington

Funding | See funding section

The rivers and land also support biologically and culturally important fish and wildlife. The southernmost district in the Forest―the Snoqualmie Ranger District―covers parts of the watersheds of the White and Greenwater Rivers. These rivers provide important habitat for salmon, steelhead, and other native fishes. Salmon are important to the local community and tribes, such as the Tulalip Tribes and Muckleshoot Indian Tribe.

In the 1994 Northwest Forest Plan, the Greenwater and Upper White Watersheds were listed as Tier 1 key watersheds. This means they play an important role in the conservation of at-risk salmon species. Also, the spring run of Chinook salmon in the White River is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Because the rivers are important to the functioning of the Forest, managers are working to keep these systems healthy now and into the future.

Historical land use effects

Like many national forests, the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest is affected by historical land use. Many streams and rivers across the Forest were disconnected from floodplains and in-channel large wood was removed because of historical misunderstandings of the best ways to reduce flooding and erosion. This made many rivers and streams very efficient in draining themselves, making them unable to store enough water in connected aquifers during times of low flow.

In addition, the Forest built over 2,000 miles of roads to access timber. Many of these roads were constructed in areas that intersected streams and affected the functionality of rivers. For instance, many roads were originally built in valley bottoms and through floodplains, preventing channels from migrating through valley bottoms. In turn, this disrupted the rivers’ ability to maintain aquatic habitat. Because the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest has so many roads, the Forest cannot maintain adequate drainage on every road. Many roads have fallen into disrepair, meaning they are more likely to fail during extreme rain events.

Roads were also built without a thorough analysis of the impacts the rivers and roads would have on each other. Richard Vacirca, the Forest Fisheries Program manager working on the Snoquera Landscape Analysis Project, says “When they built the infrastructure, they built it in the wrong places and didn’t account for watershed functionality.”

Many visitors have caused damage when not using designated roads, trails, and campgrounds (unmanaged recreation). Dispersed camping in the Forest has led to significant damage in some areas, especially in sites that were established in floodplains or riparian areas along waterways. Unmanaged user-created off-highway vehicle (OHV) trails add to the damage in the Forest.

Climate change effects on hydrology, streams, and roads

In 2014 North Cascadia Adaptation Partnership (NCAP) performed a vulnerability assessment for the North Cascades region. This assessment highlighted future climatic changes to the region, showing that this region will become warmer, affecting the snow-dominated watersheds of the North Cascades. Many of watersheds in the region will change from being snow dominated to rain dominated. This change is expected to lead to higher peak stream flows and more fall and winter flooding. It will also lead to lower summer low flows. Changes to streamflow patterns will have cascading effects throughout the Forest.

The assessment showed that changing streamflow and precipitation patterns will have larger impacts on parts of the forest where historical management decisions led to significant changes in rivers and streams. Water that moves too quickly during floods moves even faster in degraded rivers. This can cause more intense flooding during large storms and drier times in the summer.

The effects of climate change on roads located near rivers and streams could be severe. Over 300 miles of roads are in watersheds that may see a 50% increase in the size of 100-year flood events (floods so large that statistically, they should happen only once every 100 years) by 2040. High flows could block or destroy culverts and bridges that are too small to pass large volumes of water (and debris). This could cause complete road failure and damage to stream channels.

When roads fail, they input large amounts of sediment into streams and rivers. This can cause debris flow or blockages at crossings, degrading aquatic habitat. The impacts of debris flows, blockages, and destroyed road crossings can be additive. Karen Chang, the fish biologist for the Skykomish and Snoqualmie Districts, says, “Damages to road crossings on the main stem can cause blowouts farther down the river. It’s happened before. A road crossing failed high up in the watershed and the material traveled downstream. As it traveled, it destroyed the next two crossings.”

Changes to precipitation patterns will also affect soil moisture. Winter soil moisture will likely increase because of more precipitation falling as rain and more intense winter storms. This, in turn, could increase landslide hazard at higher elevations during winter and spring, damaging roads.

The Snoquera Landscape Analysis Project: preparing for the future

To prepare for the future, the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest is incorporating climate change considerations into current planning. One project that is helping them prepare is the Snoquera Landscape Analysis Project. The majority of the work on this project is focused in the Upper White River watershed (recall that this is one of two watersheds, the Greenwater and the Upper White River watersheds, in the Snoqualmie Ranger District of the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest). Much of the work on this project focuses on repairing and decommissioning (removing from active use) roads, restoring rivers, and improving river infrastructure (i.e., culverts and bridges). It aims to restore river function while accounting for current use and incorporating climate change considerations.

For projects like the Snoquera Landscape Analysis, resource managers are using the 2014 vulnerability assessment to set priorities. Following the 2014 vulnerability assessment, the Forest and its partners did an in-depth analysis of the impact climate change will have on roads. This analysis provided a first-of-its-kind resource to guide subsequent project planning and road management planning.

Vacirca says “In the face of climate change, a non-functional watershed with a high percentage of roads in it is at risk. That watershed can drain too efficiently, like a series of pipes. We want to understand what we can do to move away from those types of large-scale impairments. We want to make the watershed more resilient.” He also notes the project aims to correct the legacy impact from when roads were built. These roads have had a cumulative impact over several decades on the physical processes in the rivers.

For Snoquera, decommissioning unnecessary roads and stream crossings is a priority. The Forest is also stabilizing roads that will be retained in the Upper White River Watershed. After assessing which roads were crucial to keep, the Forest decided to decommission certain roads. They were able to focus on those that would cause issues in a future with higher stream flows.

Chang and Vacirca note that leadership within the Forest is aware of how important this area is for the Forest, tribes, and recreation for the local community. Vacirca stated that the Forest understands “that the road system gets everyone to critical locations for recreation and forest management. We’re not going to remove every road and take out all the related infrastructure. But we do want to maintain roads so that they allow us to coexist with watersheds' physical processes better.” Chang adds, “We wanted to maintain important roads. This includes roads that go to trailheads, are significant to tribes, and allow the Forest access for management.”

The Forest is also upsizing and removing some culverts. This work decreases the risk of culvert failures, which reduces the risk of road damage and sediment input to streams. Karen Chang said “Treating these roads, removing the culverts, and upsizing culverts will help to address the change in the flow regime. When a lot of these culverts went in, they were undersized. They are undersized for the flow regime we have now, let alone the amount of extra rainfall we may get in the future. The Greenwater watershed has a lot of rain-on-snow potential. As a result, the 100-year event keeps on increasing in size. By removing and upsizing culverts, it reduces the likelihood of road blowouts. This will prevent the contribution of all the road material that would come with it.”

Forest restoration is a key component of the Snoquera project. This includes floodplains and riparian areas damaged by unmanaged recreational use. One large project will restructure and block off certain dispersed camping areas. If left untreated, that area could erode and cause damage to streams. Another project will block off and repair unsanctioned user-created off-highway vehicle (OHV) roads. This will help to reduce damage to these places as earlier snowmelt attracts more visitors earlier in the season. It will also reduce the erosion caused by episodic flood events.

Land managers, fisheries biologists, and hydrologists are also incorporating fish habitat restoration into the Snoquera project. Higher temperatures in the future may decrease habitat available for cold-water dependent fish. Increasing stream temperatures can lead to fish die-offs in warmer months. Restored riparian areas can grow plants that will shade and cool rivers and streams. This will provide cold-water refugia for sensitive species in the future.

Richard Vacirca says “Rivers in the lower basin have undergone large-scale modification. For native salmon, bull trout, and cutthroat trout in the Puget Sound, restored watersheds will be important cold-water refugia. If we can do restoration on a watershed scale, we will create places where fish will be able to escape to and survive. They won’t need to face the cumulative impacts coming at them from developed land and climate change.”

Challenges and opportunities

One challenge with the Snoquera project is the inability to do restoration everywhere it is needed because of land ownership patterns in the Snoqualmie Ranger District. The land in the Greenwater watershed is a checkerboard of private and public lands, which can create challenges for management. Richard Vacirca says, “The Greenwater needs watershed and aquatic restoration, but that is challenging. A road may be a Forest Service road in this area, but other property owners rely on these roads to reach their land. You’re limited on your ability to make more progressive change. Choices about decommissioning or moving roads are more challenging with these land ownership patterns.”

The Snoquera Project has created many opportunities. It has helped the Forest create better partnerships with local non-governmental organizations and tribes. Conservation Northwest, Washington Trails Association, Trout Unlimited, and South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group have played crucial roles in helping the Forest complete these projects. This work has helped to connect people to the land and resources they care about. Also, the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe and the Puyallup Tribe of Indians have provided important input on project design. Karen Chang said, “The Forest is pretty limited in capacity to do these projects ourselves. It’s been great that we’ve had partners that have wanted to work with us. Without them, we wouldn’t have been able to get these done at the pace we’ve been able to.”

In addition, this type of whole-watershed restoration that integrates climate change is the first of its kind. The work being done in projects like the Snoquera Project have created the opportunity for the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest to become an example for other forests to follow. By showing how a national forest can us a climate change vulnerability assessment to inform road management and watershed restoration, the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest is setting an example for other forests around the country. This work allows other national forests to see the importance of moving away from a classical land management approach, where forests are managed according to historical conditions. Vacirca says, “If we only follow a classical land management approach, it may be hard to address climate change issues. Our management has to be more thoughtful and more strategic. It has to incorporate current science with the perspectives of communities, Tribes, and the State.”

- Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest Sustainable Roads System Analysis

- Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the North Cascades region, Washington

- Snoquera Landscape Analysis Summary and Resources

- Conservation Northwest Feature

- Conservation Northwest Analysis

- Washington Trails Association Feature

- Seattle Times Feature

- Honorable mention from 2020 National Climate Adaptation Leadership Awards from NFWA

- Legacy Roads and Trails