On November 2, 2023, it was standing room only for the 38 agriculture and forestry service providers attending 'Climate Smart Practices: Agroforestry – Alley Cropping and Silvopasture' education and training session at Meach Cove Farms in Shelburne, Vermont.

In partnership with NRCS-Vermont, Interlace Common, and Meach Cove Farms, Suzy Hodgson developed the Climate Learning “Healthy Trees” pilot session as part of the Northeast Climate Hub’s Climate Learning Forum. This event followed the Heathy Trees gathering in June which was the first in-person event of the Forum. The November pilot session was designed to address the management of healthy trees in climate smart practices with the focus on two USDA agroforestry practices: alley cropping and silvopasture.

Agroforestry is defined as the intentional and deliberate integration of woody vegetation (trees and shrubs) with agricultural crops and/or livestock on a land management unit to create environmental, economic, and social benefits.

The USDA defines five categories of agroforestry practices: 1) riparian forest buffers along waterways, to improve or establish vegetated areas along streams and other water bodies to stabilize banks, reduce nutrient runoff, and provide shade that lessens rising stream temperatures; 2) alley cropping, where trees are planted in rows within which crops are produced; 3) windbreaks in which trees or shrubs are grown in linear configurations alongside crops, to reduce wind velocity, decrease erosion, and improve soil; 4) silvopasture systems consisting of the sustainable production of livestock, pasture, and trees, on the same unit of land, allowing trees to be managed for timber or other tree crops while providing shade, shelter, and forage for livestock; and 5) forest farming systems whereby non-timber crops including food, medicinal, herbal and decorative are grown under stands of trees or shrubs.

This pilot session’s objectives were to 1) increase awareness of USDA CSAF (Climate Smart Agriculture & Forestry) practices, which now include agroforestry practices, and 2) increase knowledge of two of the more in demand agroforestry practices: alley cropping and silvopasture. An additional objective of the Northeast Climate Hub was to consider how this new pilot in Vermont could be offered in other states in the region to achieve similar learning objectives. For this first pilot, Meach Cove Farms proved a good location for climate smart learning because UVM Extension had recently completed a Climate Smart assessment where agroforestry was one of the recommendations for the many benefits it can provide. The training included a classroom component which covered definitions, principles, and practices of agroforestry; design considerations; site specifics; and potential tensions and tradeoffs. The classroom talks were followed by a site walk on the farm providing opportunities to view two different site locations where agroforestry could be implemented.

'Climate Smart Practices: Agroforestry – Alley Cropping and Silvopasture' education and training session at Meach Cove Farms in Shelburne, Vermont. | Photo by Nate Hodgson-Walker

'Climate Smart Practices: Agroforestry – Alley Cropping and Silvopasture' education and training session at Meach Cove Farms in Shelburne, Vermont. | Photo by Nate Hodgson-Walker

For a management practice to be called agroforestry, it typically must satisfy the four "I’s” – intentional, intensive, integrated, and interactive.

As an example, in the agroforestry practice of silvopasture, there is intentional planting and management of trees, integrated with intensive rotational grazing of animals, where there is an interactive symbiosis of growing trees, crops and grazing livestock, where each component benefits each other.

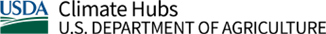

Inherent in this definition is the balancing the different components, whether trees and different crops in alley cropping or trees, livestock, and forage in silvopasture. For silvopasture, Eli Roberts, the agroforestry planner at Interlace Commons showed the ‘sweet spot’ of silvopasture as a Venn diagram with trees, grasses, and grazing animals. During the session, this practice prompted questions - “how many trees should there be per acre?”, “what species of tree work best?” and “what about the number animals per acre?”. While many participants were eager to jot down answers to these questions, there’s not one number, one best species, or one right herd size. In other words, there are many possible answers. During the session, Roberts emphasized the importance of the silvopasture process which he outlined as follows: “1) Start with the function you want the trees to serve; 2) Figure out what is appropriate for the site; 3) Then decide the species which match those criteria.” As John Van Hoesen, NRCS-Vermont described agroforestry in practice, “There is not a one size fits all.”

Both a site’s existing resource conditions and a farmer’s goals are significant factors in agroforestry implementation. Each farm operation and site will have different sets of constraints and opportunities for implementing agroforestry practices. Because farms in the northeast are so diverse in size, operations, soil conditions, topography, water availability, existing vegetative and tree cover, it’s difficult to make universal recommendations about design. Because of this, this pilot session focused on process, parameters, goals, and methods. To make this point clearly, Roberts developed and showed participants a silvopasture diagram with red and green zones. While there’s a temptation to look for a precise formula to find the number of trees per acre and size of the livestock herd, Roberts suggests instead, to think about the concept of “functional guardrails.” Diagram 1 shows that the functionality of a system matters more than identifying a “correct” number for trees or stocking rates.

Diagram 1

Diagram 1 Source: Interlace Commons

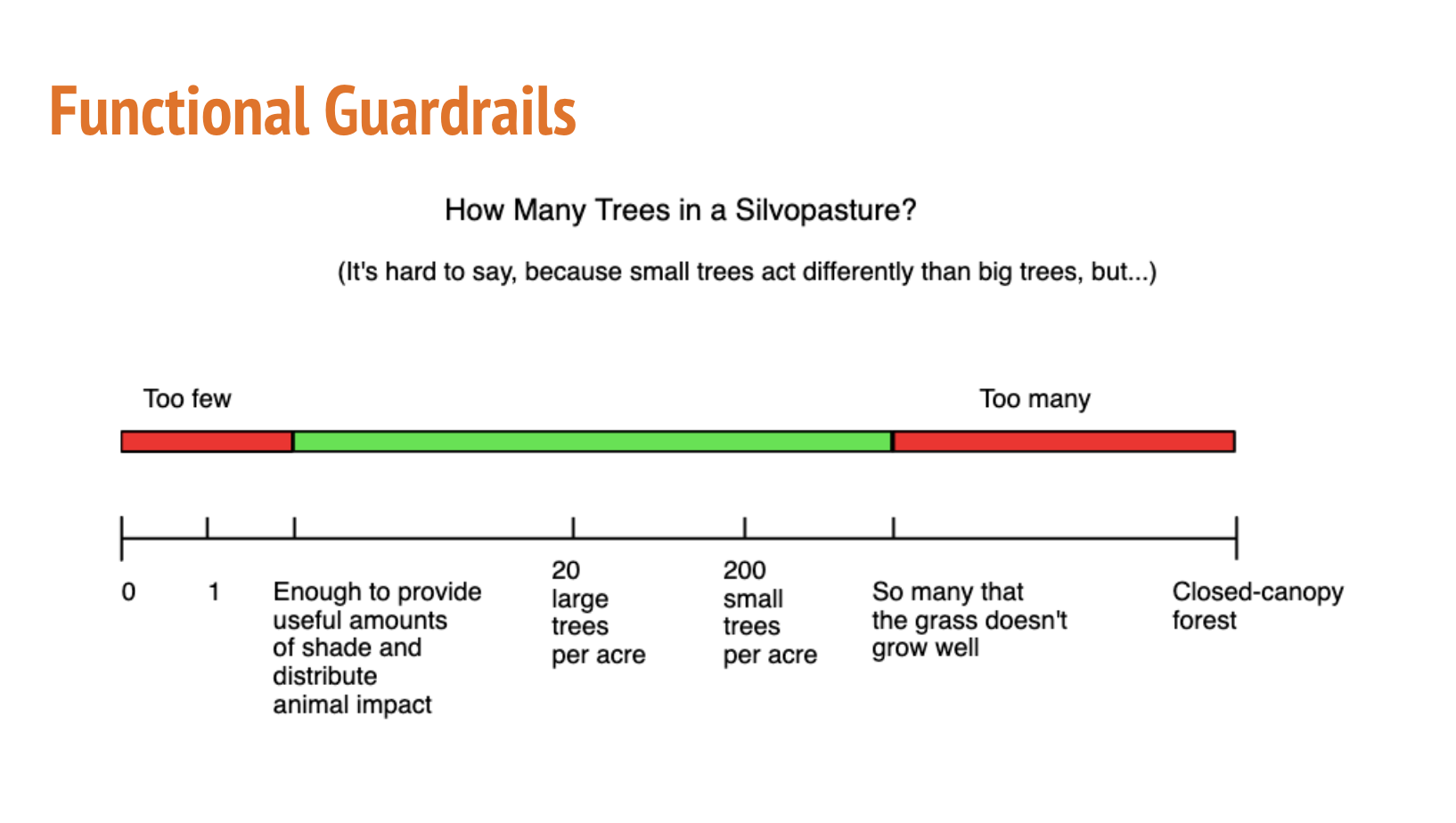

Part of this process is learning about the interactions of grazing livestock and growing trees. Examples of interactions are knowing when to move animals before they overgraze and how to protect young trees from being munched and trampled to death. Importantly, these interactions impact the productivity and economics of an agroforestry system. This is because the design process and planting of an agroforestry system typically has higher costs than a conventional system. However, over time, both the economic and the ecosystem benefits should surpass those delivered by conventional systems (Diagram 2).

Diagram 2

Diagram 2 Source: Interlace Commons

All in all, as Roberts said, “This makes it hard for people to just take a design off the shelf, which I think can be unsatisfying at first. I do think, ultimately, that these process-based designs are a better way to get more and better agroforestry on farms.” He adds, “As with any natural resource problem, it’s about managing people's goals, values, and risk tolerances, as much as it’s about planting trees and keeping them alive.” As the skies darkened at the end of the day, participants left the field as the formal session closed, leaving some open questions. Importantly, this pilot session has led to on-going discussions and interest in diving into some technical, economic, and practical aspects of agroforestry. There’s more work to done. We will continue to explore big questions like, “How productive can agroforestry systems be in a northeast?” at upcoming educational and discussion sessions.

The next scheduled event of the “Healthy Trees initiative” is an online presentation and discussion on Thursday, February 15 from 1 pm to 2 pm. Katherine Favor, ORISE Fellow, National Agroforestry Center, will introduce the topic of “overyielding” in agroforestry to frame a discussion of productivity. Overyielding is when an agroforestry system produces more than its individual components if they were managed separately. If you’d like a Teams invitation to the “Healthy Trees” discussion group, contact suzyhodgson@uvm.edu.

References:

- Garcia de Jalon, S., Graves, A. R., Palma, J. H. N., Crous-Duran, J., Giannitsopoulos, M., & Burgess, P. J. (2017). Modelling the economics of agroforestry at field-and farm-scale

- Interlace Commons

- USDA Agroforestry Strategic Framework, Fiscal Year 2011-2016

- USDA | Agroforestry

- USDA National Agroforestry Center

- UVM Extension Center for Sustainable Agriculture